One Key Strategy to Sustainably Elevate Social Determinants of Health & Substantially Reduce Numerous, Escalating Expenses for Providers & Funders

Share this pageBrief About

The drumbeat is loud and clear. Jobs, volunteering, community engagement, social capital, and wellness activities for people with disabilities are imperative. But there’s a formidable roadblock getting in the way of this popular, well-intentioned goal. Value-based and managed care expectations, for quality and funding reasons, are insisting on change and assigning responsibility. Clinical well-being—the catalyst and prerequisite to improved social determinants of health—is woefully subpar, and there is a lack of recognition for its linchpin role as the first, all-important step. To put the cart before the horse has always oozed futility, and it does in this instance, as well. After all, if you keep calling in sick to your employer, you will not hold down that pivotal job. Nor will you join your walking club or meet your friend for coffee if you don’t have the energy to move.

Overall Clinical Health & Financial Picture within the Industry

While looking for a fix to this monumental problem, it’s important to understand the overall landscape regarding clinical health within the IDD industry. Approximately 70% of people with disabilities are unnecessarily struggling with out-sized, poor health as a result of obesity, overweight and underweight status, diabetes, hypertension, and a host of additional chronic conditions. This subpar state is evident in LTSS/MLTSS settings among people with IDD, TBI, SPMI and behavioral challenges.

Based on recent external research studies, health care costs for people with IDD are high and expanding quickly. The annual medical expense for a person with a disability living in a community-based setting ranges between $25,000 and $40,000. People with IDD comprise 1% of the Medicaid case load and 11% of Medicaid’s expense; the lopsidedness rests squarely on the shoulders of health care cost. While providers aren’t yet on the hook for acute care and medication expense, the looming sonic boom of a single capitated rate, managed care, and value-based expectations is shifting responsibility to the first line of preventive health delivery; human services organizations are unwittingly, but inexorably, morphing into health care entities.

With constant or declining LTSS rate reimbursement and health care costs likely increasing at almost double-digit annual rates, there will be a crossover point in the not-too-distant future.

For providers in states with low LTSS reimbursement rates, the crossover point—aggregate health care costs for people supported exceeding LTSS expenses—will occur in approximately three years. We estimate the crossover point will occur for all states and providers within the next five years. Consequently, from a cost and funder perspective—IDD services will absolutely be entrenched in the health care business.

It appears to be an inevitable trend that MCOs will contract (as administrators and payers) with increasing numbers across state Medicaid services. There are simply too many lives to cover and too much money at stake to prevent MCOs from finding a path to success in this market. MCOs have a core competency related to squeezing costs out of a system – primarily through tough rate negotiation and zeroing in on all areas of expense reduction. Additionally, “playing” one provider against another provider is another winning approach MCOs historically bring to the cost-cutting table. Using these tactics in the IDD space is a logical, anticipated game plan.

MCOs well understand that a large percentage of health care costs are due to preventable behaviors. Recent studies indicate that 13% of all early and unnecessary deaths are due to nutrition or the foods that people consume. Additional, ongoing studies are confirming that at least 10 – 15% of all health care costs can be forestalled (pushed into future years), or completely eliminated, via improvements to nutrition; this area of cost containment will become a laser focus for MCOs. Our own long-running experiences demonstrate that improved nutrition alone substantially and sustainably moderates poor health among people with IDD.

LTSS providers are an easily identifiable target as the most likely change agent. In most cases, these organizations are directly responsible for procuring and preparing meals for people supported. Or, the provider is responsible for helping people supported make informed and responsible choices regarding food consumption. There is recognition within the industry regarding this responsibility and opportunity to intervene; a respected IDD provider in the Midwest notes: “Choice does not mean helping a person supported eat themselves into a poor quality of life and early death.”

Zeroing in on the Roadblock to Elevating Social Determinants of Health

Despite what has long been ascribed to the genetics of the disability or pharmacological complications, poor clinical health is increasingly and clearly being ascribed to preventable poor nutrition among people with IDD. Funders, including the American public, are on a slippery slope underwriting non-nutritious foods and then resulting poor health and quality of life.

That it takes one hour of vigorous exercise to burn off a can of soda pop is perhaps the most compelling example of why the problem has to be addressed through food—eating is a daily must for everyone. We typically see physical activity that is beneficial for cardio, flexibility, and balance purposes accelerate among people with disabilities—as is the case within the mainstream—once a healthy weight is achieved via enhanced nutrition.

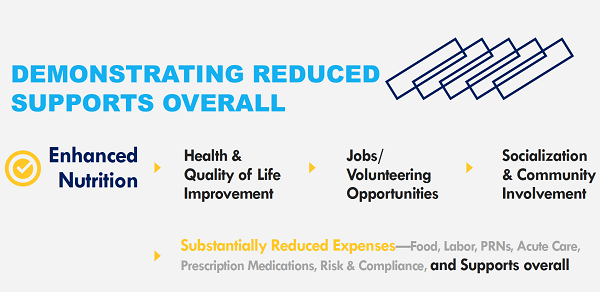

As highlighted below, it’s being demonstrated daily that once the first domino—enhanced nutrition—is in place, the remaining dominoes follow in favorable progression . . . elevated social determinants of health and reduced supports overall. Within 6 to 12 months, the dismal statistic we noted above reverses and sustains so 70% of people supported are at or moving toward a normal BMI, with additional health parameters—such as A1c levels, blood pressure readings, and medication dosage/usage—showing similar improvement.

Across the entire industry, this translates to a potential several billions of dollars of savings on an annual basis—monies that can be more purposefully and admirably put toward enhanced nutrition, preventive clinical health, and social determinants of health elevation.

The One Key Strategy

The one key strategy to improving social determinants of health for people supported depends on improved clinical health, which hinges on enhanced nutrition. We know there are those of you who are champing at the bit to be heard as you refute the possibility of improved nutrition for people supported. We address the most oft-mentioned opposition below—providing insight and hopefully a pathway toward understanding that the job is hard, but no longer impossible, unaffordable, or deferrable. Essentially, you can get it done . . . and should.

But . . . Person-Centered Choice!

In our ongoing conversations with CMS, we clearly hear that the intention behind person-centered choice is based on responsible choice, rather than allowing the individual supported to eat themselves into life-threatening illness. Further, it’s not out of line for funders to have the reasonable expectation that there is honorable stewardship regarding monies invested in this vital population—as in not creating, nor sustaining, that slippery slope noted above.

One Midwest provider CEO pointed out that, all too often, those most protesting a violation of person-centered choice are really working hard to preserve DSP choice . . . what staff can prepare or wants to prepare. Interestingly, health is typically most compromised in these settings.

Debate-worthy arguments aside, there are resources available these days for LTSS settings that clearly and succinctly detail how to substantially improve nutrition while preserving person-centered choice. What is particularly encouraging is that these resources also include a road map for helping consumers buy into eating the right foods in the right amounts and engage with mealtime planning/preparation; as a result, choice more seamlessly evolves into responsible, informed choice. “When you make it, you own it.”

But . . . Food Costs & Reimbursement!

Grocery expense totaling $3.95-$4.50 per person per day for all meals, snacks, and beverages in an LTSS setting—on a person-centered choice basis—has now been proven to deliver beneficial nutrition for people supported . . . as in, healthier foods do not have to cost more than unhealthy options. What astounds the industry is that achieving $3.95-$4.50 pp/day is not largely a result of per food item cost reduction. Rather, adherence in the grocery store to well-constructed, healthy, choice-based, and perpetually refreshed (as in routinely picks up on census changes and seasonal pricing) menus is the answer.

But . . . Staffing Challenges!

Challenges recruiting, retaining, educating, and fostering job satisfaction regarding DSPs and house managers are among the greatest of obstacles as far as improved nutrition for people supported. The difficulty lies not with DSPs as people, but with the lack of a system and/or process. A system that can be executed in a foolproof way—regardless of personnel turnover or inexperience—and that holds staff accountable. The job is too demanding and multi-pronged for the industry’s bright and earnest dietitians; longstanding, poor health statistics regarding people with IDD bear this out.

Based on our years of experiences in thousands of LTSS settings, this is an area where industry leadership can step up. Despite being what is typically an organization’s 4th highest expense category, rife with risk and compliance exposure/pay-out, and the number one culprit behind 70% of this vital population moving away from a normal BMI, food is not addressed strategically by most human services providers. Food might be handled the same way procurement buys washing machines for its community-based residences in some organizations, but few CEOs are calling a management meeting to map out holistic and process-oriented improvement to mealtime and preventive health in their LTSS settings.

The good news is that there are foolproof mealtime systems available that are synergistic with health improvement, person-centered choice, reduced food costs, and a streamlined mealtime process for DSPs. Still, the DSP will be required to do more than put a frozen pizza in the oven and can’t be allowed to shrug their shoulders and say, “I don’t like this change and therefore it should trump the immediate and long-term (more than the average tenure of a majority of DSPs) health of people supported.”

And given that there is just so much any outside resource can impart regarding a cultural shift within the organization, provider leadership will have to instill enthusiasm and the expectation, while weathering a storm or two of protest, by holding steady to: “This is the new way of handling preventive health for the people we support, and it’s no longer an option to do otherwise. Until you come up with a better outcomes-oriented strategy to improve immediate and long-term health, we’re tackling this at mealtime in a strategic way now.” This is exactly what managed care and Medicaid officials are trumpeting.

But . . . Doctor Visits, We’re On It!

Providers are up to speed on a number of necessary checkmark items, such as routine doctor visits and managing medications. No small feat given all the moving parts and dynamics involved. There are also attempts at corrective action when the poor health alarm bell goes off, such as: “Get some exercise, ” “Get health risk screening,” and “See a dietitian.” But most of this is centered on outputs, the primary measurement and mode of operating within many provider organizations . . . and put forth by a number of risk assessment, regulatory, and accreditation bodies. Conversely, an outcomes orientation centers on actual, objective results and action plans to zero in on appropriate remediation.

A seismic shift toward an outcomes model is needed throughout the human services industry in order to foster meaningful, clinical health improvement for people supported. There are resources today that accelerate and install an outcomes approach regarding preventive health and enhanced nutrition . . . including realistic and budget-friendly action plans for each individual supported.

But . . . Families/Guardians!

We’ve always remained polite and professional, but we admittedly scratch our heads when human rights groups and family members protest a person-centered choice, healthy change in mealtime. Similarly, we’ve been on the firing line where guardians have cried foul when we rebalance nutrients on the plate and up daily fiber synergistic with USDA recommendations. But we have yet to meet one person in the thousands of people supported we’ve helped improve their clinical health who have been angry or dissatisfied with their elevated social determinants of health and cool-looking jeans.

There are resources available today that engage family members and guardians, so that everyone associated with the person supported can be on the same page as far as eating the right foods in the right amounts. Not surprisingly, family members and guardians are simultaneously improving their health as a result.

In Sum

We all want to elevate social determinants of health for people with disabilities. As the graphic on page three highlights, this is how multiple benefits accrue to multiple stakeholders. In order to achieve the goal, however, the industry has to first recognize and surmount the major obstacle getting in the way of jobs, volunteering, community engagement, social capital, and wellness activities.

We all want to elevate social determinants of health for people with disabilities. As the graphic on page three highlights, this is how multiple benefits accrue to multiple stakeholders. In order to achieve the goal, however, the industry has to first recognize and surmount the major obstacle getting in the way of jobs, volunteering, community engagement, social capital, and wellness activities.

Clinical health and improved nutrition must be priority one given that 70% of this vital population is currently moving away from a normal BMI and unnecessarily struggling with elevated and costly rates of diabetes, hypertension, and associated chronic conditions; these debilitating circumstances make it virtually impossible to progress forward on any productive front.

Fortunately, there are robust, affordable resources available to help providers and managed care organizations address age-old stumbling blocks and objections, making the job doable and easier. But industry leadership will have to step up and, in most cases, toughen up . . . shifting its mindset from “defer” to “now” and from outputs to outcomes. There is no question that a hands-on, person-centered, strategic focus regarding mealtime and preventive health is the call to action. In this way, monumental change from a quality and financial standpoint will finally have a chance to take hold and sustain—elevating social determinants of health for people supported and benefitting key stakeholders.

Watch: How to Implement Strategic Mealtime (on your own!—providers, ACOs and MCOs)

Jim Vail and Sylvia Vail both hold their MBAs from Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management and both are long experienced, with a track record of unique successes, in the health care and human services industries. They have an impressive background spearheading critical health improvement, person-centered choice enhancement, nutrition elevation, and expense reduction (food, labor, PRNs, acute care, prescription medications, risk and compliance) outcomes achievement across thousands of LTSS settings, throughout the U.S.

Jim Vail and Sylvia Vail both hold their MBAs from Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management and both are long experienced, with a track record of unique successes, in the health care and human services industries. They have an impressive background spearheading critical health improvement, person-centered choice enhancement, nutrition elevation, and expense reduction (food, labor, PRNs, acute care, prescription medications, risk and compliance) outcomes achievement across thousands of LTSS settings, throughout the U.S.

Sylvia and Jim are co-founders of Mainstay, Inc. and its My25 programs centered on Strategic Mealtime & Technology-Supported Mealtime for human services entities supporting people with IDD, SPMI, TBI, and behavioral challenges. Mainstay’s foundation was built in partnership with the USDA and through collaboration with professionals from the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University. The World Health Organization recently substantiated My25’s approach to nutrition enhancement for people with IDD as the fundamental solution behind improved health and reduction of multiple chronic conditions—leading to better quality of life and more robust opportunities.

Sylvia and Jim are co-founders of Mainstay, Inc. and its My25 programs centered on Strategic Mealtime & Technology-Supported Mealtime for human services entities supporting people with IDD, SPMI, TBI, and behavioral challenges. Mainstay’s foundation was built in partnership with the USDA and through collaboration with professionals from the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University. The World Health Organization recently substantiated My25’s approach to nutrition enhancement for people with IDD as the fundamental solution behind improved health and reduction of multiple chronic conditions—leading to better quality of life and more robust opportunities.

Sylvia can be reached at [email protected]. Jim can be reached at [email protected].